A highly anticipated legal battle is underway in the North Gauteng High Court today (1 November 2016). President Jacob Zuma, Mineral Resources Minister Mosebenzi Zwane and Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs Minister Des van Rooyen are seeking to interdict (prevent the disclosure of) former Public Prosecutor, Thuli Madonsela’s findings on the so-called #StateCapture allegations.

Briefly, State Capture can be definedas the systemic political corruption in which private interests significantly influence a state’s decision-making processes to their own advantage.

Broadly, there are two types of interdicts – interim and final. I have not had the opportunity to review the court papers, but be that as it may, this article briefly explores South African civil procedure relating to interdicts.

Holistically, an interdict is a court order prohibiting certain conduct (prevents the respondent from doing something) or forcing certain conduct (requires respondent to do something). For example, the interdict in the #StateCapture matter will ask the court, via an application with supporting affidavits, to prevent the Public Prosecutor from releasing her controversial report on the influence held by the politically connected Gupta family.

The requirements for an interdict are:

Interim interdict

- prima facie right

- Well-grounded apprehension of irreparable harm

- No other satisfactory remedy

- Balance of convenience favours the granting of order

Final interdict

- Clear right

- Injury suffered / reasonably apprehended

- No other satisfactory remedy

Consequently, the applicants in court today must show that a right exists. A prima facie right, is a right that exists “on the face of it” – it doesn’t matter where the right comes from, be it from a contract, the common law or in terms of a statute, but it must be an actual right; a mere interest in the relief sought is not enough.

Secondly the applicants must show there is a well-grounded apprehension of irreparable harm. “Irreparable” alludes to a situation where the harm is difficult/impossible to restore. Similarly, in a final interdict, the applicants must show that an injury (not necessarily physical) has been suffered, or is reasonably apprehended.

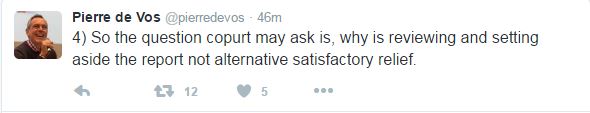

Further, the applicants must further show that there is no other satisfactory remedy in law. In my view, they may struggle to get over this hurdle. As pointed out by Professor De Vos, the Claude Leon Foundation Chair in Constitutional Governance at the University of Cape Town:

The issue alluded to above is that the applicants have the right to review and set aside the Public Protector’s report once it has been published – this (in and of itself) is probably enough to constitute a suitable alternative remedy. That said, the applicant’s will no doubt argue that if the report is published it will cause irreparable damage to their reputations.

Moreover, in an application for an interim interdict, the applicants must show that the balance of convenience favours granting the interdict. Given the right is only prima facie, it is important that the respondent should not be unfairly prejudiced – this also includes considering the prospects of success of the applicant and may include public interest. In my view, the balance of convenience (given the intense public interest and national importance to our economy and related institutions of government) does not favour granting the order.

In terms of procedure, typically, the applicant will ask for temporary relief (in the form of an interim interdict), which will operate until a further hearing, often referred to as “the return day”. Briefly, the procedure usually follows this route:

- An application for an interim interdict is brought (with supporting affidavits setting out the grounds discussed above)

- If the matter is urgent, the application may be brought ex parte (without notice to the other party), with a rule nisi (order instructing parties to return to court on a specified day in future – usually around 2-4 weeks)

- After the interim interdict (and rule nisi) is obtained, the respondent must show cause on the return day why the order should not be confirmed and a final interdict granted

- On the return day in court, the interdict sought is usually final, but may again be interim.

Millions of South Africans (as well as a few economists and currency speculators) are waiting with bated breath…

thank you for such a good read. i love how you tackle all perspectives in your articles. that makes it for everyone to read. keep doing an amazing job

LikeLike

this tussle has gone on for a whilw but I have faith in the south african justice system hoping that justice will be served its quite a coincidence I had an is my essay good on this subject for my final year project

LikeLike