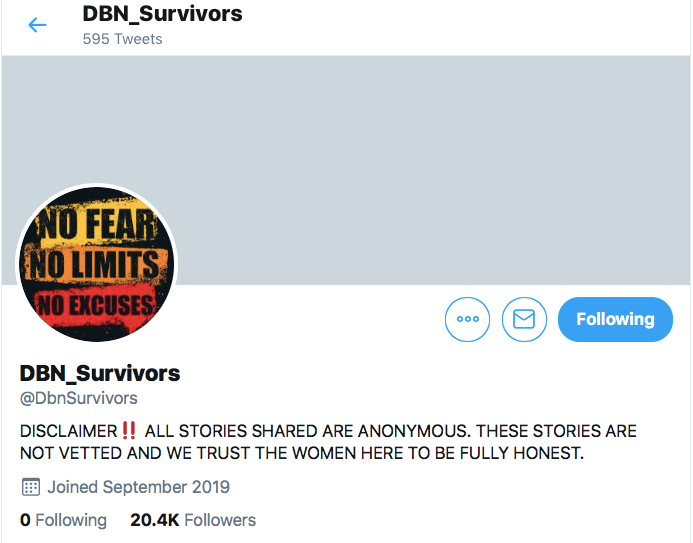

Recently, accounts on Twitter such as @AmINext_sa, @HSurvivers3, @helpsurvivers, and @DBN_survivors have posted anonymous allegations of rape and serious sexual abuse. In under two days, the Durban account has amassed almost 20 000 followers.

In the posts on these accounts, alleged perpetrators are named and shamed with full detail and pictures (in some pictures, in addition to the alleged perpetrators, their children and/or family are also visible). The victims’ details are kept anonymous.

The revelations on these pages are shocking – and makes one feel sick to the stomach. I can totally understand victims wanting to “out” their abusers, and it is sadly true many victims will never report this abuse to the police; but these types of posts violate the rights of many innocent people – lives are being destroyed; jobs are being lost.

I have seen several posts pertaining to university lecturers, celebrities, politicians, and other prominent people (in addition to many “normal” people). One should consider: what if this information is false? To be sure, sadly, I suspect much of it is true. South Africa has a massive problem. Civil society and government intervention are urgently required. But this mob justice type of vigilantism does not appreciate the rule of law, and the fact that every person is entitled to be presumed innocent until proven otherwise, and that every person is entitled to be heard, and give their account of events (as well as to provide all supporting evidence).

These are the most heinous crimes; and although the prosecution rate is worryingly low, and the legal process is fraught with delay and difficulty, South Africa is based on the rule of law. A fundamental pillar to the rule of law is that a person is innocent until proven guilty. The solution is not an easy one, but naming and shaming on social media is not the answer – particularly if a legal process has not been followed.

For those persons who have been named and shamed without justification, there are several legal remedies available. From a criminal perspective, crimen injuria (attack to a person’s dignity) and criminal defamation (attack to a person’s reputation) will be applicable. From a civil perspective, one can also rely on defamation (there is a difference between civil and criminal defamation), as well as the Protection from Harassment Act.

Recently, in Hechter v Benade, decided on 5 December 2016, the court ordered the defendant to pay R350 000.00 in damages for defamation, plus legal costs and interest for naming and shaming – this in my view was far less serious than what is happening on Twitter over the past few days…

The owner’s and administrator of the account cannot hide behind a half-baked “disclaimer”. And the identity of those persons behind these accounts can be established – most things on the internet can be verified with some effort, especially if one obtains a court order.

In South African law, any person who publishes or re-publishes defamatory or objectionable content can be held liable. In Tsedu v Lekota, the City Press was ordered to pay R100 000.00 damages to a politician for accusing him of spying. The media publication alleged they were simply repeating what someone else said (as is the case on Twitter now). The court rejected this, and endorsed the following:

‘[a] person who repeats or adopts and re-publishes a defamatory statement will be held to have published the statement. The writer of a letter published in a newspaper is prima facie liable for the publication of it but so are the editor, printer, publisher and proprietor. So too a person who publishes a defamatory rumour cannot escape liability on the ground that he passed it on only as a rumour, without endorsing it.’

See also, Dutch Reformed Church Vergesig Johannesburg Congregation v Rayan Sooknunan t/a Glory Divine World Ministrieswhere the administrator of a Facebook Group was liable for content on that group. Further, in Isparta v Richter, the issue was whether a person can be liable for posts she did not create, but where she was tagged in the post. The court found that the defendant was aware, or ought reasonably to have been aware (allowed name to be coupled with defamatory content). This decision is consistent with the principle that everyone who repeats, confirms, or draws attention to a defamatory statement will be held responsible for its publication.

Consequently, if a person is named and shamed on one of these Twitter groups, and they believe the allegations are false, they can take legal action – criminal and civil.

The authors of these pages may face serious legal difficulty; in addition to the above, the Criminal Procedure Act provides that an accused should not be named until such time as they have pleaded to the charge. It is unclear whether the matters on the Twitter groups are being investigated by the police and/or whether there are any charges pending – in most cases, it seems no report has been made to the police. That notwithstanding, section 154 (2) (b) of the Criminal Procedure Act provides as follows:

No person shall at any stage before the appearance of an accused in a court upon any charge referred to in section 153 (3) [this refers to sexual offences and/or rape] or at any stage after such appearance but before the accused has pleaded to the charge, publish in any manner whatever any information relating to the charge in question.

Section 69 of the South African Police Services Act also prohibits pictures of an accused being published – but only if the person is in custody (not applicable I suspect to any of these Twitter cases).

Although the police, and society at large need to do more, this type of electronic vigilantism – a form of lynch-mob – should not be endorsed. The rule of law and due process must be followed. Several innocent people are being burned alive at the stake in the name of justice – as I see it, there is no justice in that…