The preamble to South Africa’s Constitution defines the nation as one that is united in diversity – it further sets out the basis for a non-racial democracy. Given South Africa’s traumatic and racist history, the new constitutional dispensation is based on values of freedom, equality, and dignity. The preamble reads in full as follows:

We, the people of South Africa,

Recognise the injustices of our past;

Honour those who suffered for justice and freedom in our land;

Respect those who have worked to build and develop our country; and

Believe that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity.

We therefore, through our freely elected representatives, adopt this Constitution as the supreme law of the Republic so as to –

Heal the divisions of the past and establish a society based on democratic values, social justice and fundamental human rights;

Lay the foundations for a democratic and open society in which government is based on the will of the people and every citizen is equally protected by law;

Improve the quality of life of all citizens and free the potential of each person; and

Build a united and democratic South Africa able to take its rightful place as a sovereign state in the family of nations.

May God protect our people.

Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika. Morena boloka setjhaba sa heso. God seën Suid-Afrika. God bless South Africa. Mudzimu fhatutshedza Afurika. Hosi katekisa Afrika.

Freedom of expression is jealously protected in South Africa – it is said to exist for the proper functioning of democracy; to ensure individuals and society can search for the truth; and for achieving individual self-fulfilment and autonomy (for further detail, see D Milo and P Stein, A Practical Guide to Media Law).

The Constitutional Court, in South African National Defence Union v Minister of Defence, stated as follows in relation to freedom of expression:

Freedom of expression lies at the heart of a democracy. It is valuable for many reasons, including its instrumental function as a guarantor of democracy, its implicit recognition and protection of the moral agency of individuals in our society and its facilitation of the search for truth by individuals and society generally. The Constitution recognises that individuals in our society need to be able to hear, form and express opinions and views freely on a wide range of matters.

However, freedom of expression is not absolute – the basis of this inalienable right is set out in section 16 of the Constitution, which provides as follows:

(1) Everyone has a right to freedom of expression, which includes-

(a) freedom of press and other media;

(b) freedom to receive and impart information or ideas;

(c) freedom of artistic creativity; and

(d) academic freedom and freedom of scientific research.

(2) The right in subsection (1) does not extend to –

(a) propaganda for war;

(b) incitement of imminent violence; or

(c) advocacy of hatred that is based on race, ethnicity, gender or religion, and that constitutes incitement to cause harm.

Section 16 therefore sets out the scope of the right to freedom of expression – it broadly protects freedom of expression(which is wider than speech), and lists express protection for categories of expression that will be protected, such as in the media and academia. However, section 16(2) also clearly excludes certain categories of speech from protection under this right – such as hate speech. As noted in the seminal case of Islamic Unity Convention v Independent Broadcasting Authority:

Section 16(2) therefore defines the boundaries beyond which the right to freedom of expression does not extend. In that sense, the subsection is definitional. Implicit in its provisions is an acknowledgment that certain expression does not deserve constitutional protection because, among other things, it has the potential to impinge adversely on the dignity of others and cause harm. Our Constitution is founded on the principles of dignity, equal worth and freedom, and these objectives should be given effect to.

In order to give effect to human dignity, freedom, and equal worth, the South African legislature enacted the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act (‘Equality Act’). Primarily, as set out in section 2, the Equality Act aims to “provide for measures to facilitate the eradication of unfair discrimination, hate speech and harassment, particularly on the grounds of racism, gender and disability”.

As noted in the recent matter of South African Human Rights Commission v Khumalo, South Africa deliberately chose to limit freedom of expression – the court noted: “Plainly, complete freedom of speech is deliberately compromised, a policy choice made to address our society’s social conditions.”

As a result, the Equality Act plays an important role. It seeks to provide further flesh to the constitutional skeleton in place. Section 10 of the Equality Act prohibits hate speech – while section 16(2) of the Constitution provides that hate speech will not be afforded constitutional protection; a subtle but important distinction.

The Constitution does not prohibit or regulate hate speech, rather, it excludes hate speech from protection under the right to freedom of expression. Conversely, the Equality Act expressly prohibits hate speech – but it does not create a criminal offence for the publication or dissemination thereof, the remedy in the Equality Act is currently civil in nature (however, changes are imminent: draft legislation in the form of a hate speech bill will criminalise hate speech once passed into law – I expect this will take place in the next 12 months). Importantly, section 12 of the Equality Act contains a provision that allows journalists, academics and others to engage on these issues without fear of legal repercussion – but, the publication must be genuine and in good faith.

In addition to the above, the criminal offence of crimen injuriamay be concurrently at issue in hate speech matters (given that the Equality Act only provides a civil remedy as the law stands). The South African Police Servicedefine crimen injuria as: unlawfully and intentionally impairing the dignity or privacy of another person.

Recent South African cases dealing with hate speech

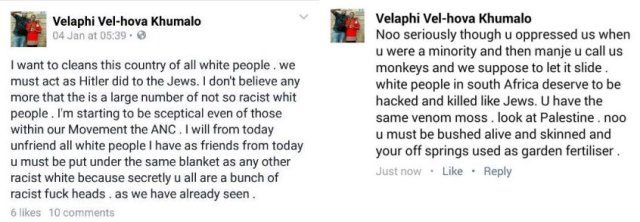

Before discussing the Old South African flag case, for further context, consider the two social media posts below, and an excerpt from a speech at the University of the Witwatersrand:

Expression A

Expression B

Expression C

On 5 March 2009 Mr Masuku made the following three statements as part of his speech at a gathering at the University of the Witwatersrand:

‘ … COSATU has got members here on this campus, we can make sure that for that side it will be hell …’,

… the following things are going to apply: any South African family, I want to repeat it so that it is clear for everyone, any South African family who sends its son or daughter to be part of the Israeli Defence Force must not blame us when something happens to them with immediate effect …’, and

‘… COSATU is with you, we will do everything to make sure that whether it is at Wits, whether it is at Orange Grove, anyone who does not support equality and dignity, who does not support the rights of other people must face the consequences even if we will do something that may necessarily be regarded as harm …’

In terms of expression A, in South African Human Rights Commission v Khumalo, the statements posted on social media were “statements prohibited by section 10(1) of the Equality Act”. This finding seems obvious, and precisely the type of expression that should be prohibited in the interests of nation building. The court ultimately ordered an apology, that the statements were declared to be speech prohibited in terms of section 10(1) of the Equality Act, and that the matter should be referred to the Director of Public Prosecutions. Currently, I am unable to determine whether criminal proceedings against Mr. Khumalo have been instituted, or whether the National Director of Public Prosecution declined to prosecute.

In terms of expression B, according to media reports, Mr. Kriel pleaded guilty to a charge of crimen injuria, and was sentenced to a fine of R6 000, or 12 months’ imprisonment, suspended for five years. As an aside, see further, Penny Sparrow– also charged and convicted of crimen injuria, in addition to criminal prosecution, she was also found liable by the Equality Court to pay civil damages; and Adam Catzaveloswho is facing criminal and civil action for racist comments.

In terms of expression C, in Mr. Masuku’s case, the Equality Court initially ruled in 2017 that the statements above in relation to Israel were hate speech in terms of section 10 of the Equality Act. However, this decision was appealed to the Supreme Court of Appeal (‘SCA’), and in Masuku v South African Human Rights Commission, the SCAultimately dismissed the complaint finding:

Nothing that Mr Masuku wrote or said transgressed… boundaries, however hurtful or distasteful they may have seemed to members of the Jewish and wider community. Many may deplore them, but that does not deprive them of constitutional protection.

I find this decision puzzling. Section 16(2)(b) provides that “incitement of imminent violence” will not find constitutional protection, and section 16(2)(c) excludes expression that advocates “hatred that is based on race, ethnicity, gender or religion, and that constitutes incitement to cause harm”.

The appellant, Mr. Masuku was quoted as saying: “ [they] must not blame us when something happens to them with immediate effect”; and “even if we will do something that may necessarily be regarded as harm”. The court in Masuku provides very little legal analysis to support the contention that this expression is protected by section 16. As I see it, this expression goes further than being “distasteful” – it appears, on the face of it, to suggest harm to persons based on ethnicity and/or race. The court in Masuku quoted Hotz v University of Cape Town which provided that:

a court should not be hasty to conclude that because language is angry in tone or conveys hostility it is therefore to be characterised as hate speech, even if it has overtones of race or ethnicity.

When a person directly threatens another with harm, primarily based on that person’s religion, race or culture, that is more than a speech with “overtones” – it was overt, and not merely alluded to or containing “overtones”. The speech was clear: if you go there, we will harm you. We should not allow persons who hold different opinions to be able to foist their views on society with direct threats – this compromises the very foundations of democracy. Freedom of expression should allow lively, uncomfortable and direct debate – but it should not allow victimisation and threats of imminent harm.

Further, after outlining the facts and issues in dispute, the court noted as follows:

After the complaint was made, the Commission formed a preliminary view that Mr Masuku’s statements constituted hate speech, prohibited under s 16(2) of the Constitution, and s 10 of the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act No 4 of 2000 (the Equality Act).

It is worth pointing out that section 16(2) of the Constitution clearly does not prohibit hate speech (it excludes it from protection under the right to freedom of expression). Confusingly, the court noted as follow:

during the hearing of the appeal counsel for the Commission disavowed the reliance on the Equality Act, accepting that the statements, as any other form of speech, would be excluded from protection (as hate speech) under s 16(1) of the Constitution only if they fell foul of s 16(2) thereof.

The disavowal was properly made. There is cause for concern that the provisions of s 10 of the Equality Act have the effect of condemning speech that is protected under s 16(1) of the Constitution.

In summary, the starting point for the enquiry in this case was that the Constitution in s 16(1) protects freedom of expression. The boundaries of that protection are delimited in s 16(2).The fact that particular expression may be hurtful of people’s feelings, or wounding, distasteful, politically inflammatory or downright offensive, does not exclude it from protection. Public debate is noisy and there are many areas of dispute in our society that can provoke powerful emotions. The bounds of constitutional protection are only overstepped when the speech involves propaganda for war; the incitement of imminent violence; or the advocacy of hatred that is based on race, ethnicity, gender or religion, and that constitutes incitement to cause harm. Nothing that Mr Masuku wrote or said transgressed those boundaries, however hurtful or distasteful they may have seemed to members of the Jewish and wider community. Many may deplore them, but that does not deprive them of constitutional protection.

As I see it, there is no basis in law for anyone to “disavow” the Equality Act. It binds all persons in South Africa (see section 5), and was the basis of the cause of action in the Equality Court. Even if this speech did fall to be protected, the court should have provided further analysis and justification – and it should have engaged with the Equality Act which was directly at issue, or made a finding regarding its constitutionality after engaging with the limitations clause (section 36 of the Constitution).

The SCA’s “cause for concern” is no basis to ignore the Act and its emerging jurisprudence. Section 16, as the court itself notes, limits the right to freedom of expression – there is specific legislation enacted to regulate this issue and further animate section 16 and related sections (for example, the Equality Act which speaks to the right to dignity and places limitations on freedom of expression in the context of hate speech).

If the clause is constitutionally suspect, which appears a valid concern, then the Equality Act should be properly challenged on that basis – to ignore the Act ostensibly in light of section 16 is plainly wrong, and inconsistent with earlier Constitutional Court judgments (see para 31 of Islamic Unity Convention v Independent Broadcasting Authority, where the court stated: “there is no doubt that the state has a particular interest in regulating this type of expression because of the harm it may pose to the constitutionally mandated objective of building the non-racial and non-sexist society based on human dignity and the achievement of equality.”)

As noted by Professor Pierre de Vos, the SCA seem to have incorrectly applied the law in this case:

It appears that the SCA ignored the law that applied to the case before it because of concerns that the relevant provisions of [the Equality Act] may constitute an unconstitutional infringement on the right to freedom of expression… The constitutionality of sections 10 and 12 of [the Equality Act] were not raised in this case and the SCA did not consider the constitutionality of these provisions. The SCA therefore had no choice but to apply the (for the moment, constitutionally valid) provisions of [the Equality Act]. It was therefore impermissible for the SCA to ignore the applicable law contained in [the Equality Act] and apply section 16(2) instead.

The SCA was prohibited from applying section 16(2) instead of the provisions of [the Equality Act] because of the well-established principle of subsidiarity.

This principle – confirmed for the umpteenth time in the recent Constitutional Court judgment of De Lange v Presiding Bishop of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa– holds that where legislation gives effect to a constitutional right, the litigants must rely on the underlying legislation and is not permitted to invoke the constitutional provision directly. So, even if one were to agree with the clearly wrong belief that section 16(2) prohibits hate speech, the SCA were bound by the principle of subsidiarity to apply the provisions of [the Equality Act]instead of section 16(2) of the Constitution.

Milo and Stein, in A Practical Guide to Media Law, note the following regarding this issue:

Hate speech does not attract the protection of the right to freedom of expression. Section 16(2) of the Constitution does not, however, prohibit hate speech, nor does it criminalise hate speech; it merely states that the protection of section 16(1) does not extend to hate speech. There are, however, other laws which specifically regulate the publication of hate speech [such as the Equality Act and the Films and Publications Act].

The judgment in Masuku is confusing and legally problematic, and one that I hope will be clarified in the Constitutional Court in the months to come.

The Old South African Flag case

Hate speech was again recently before the South African courts in Nelson Mandela Foundation Trust v Afriforum, where the Old Flag was at issue.

Image via Creative Commons “East London Museum” by Chris Bloom; Old Flag on the left, current South African flag on the right.

According to the judgment in this case, the Old Flag is:

for the majority of the South African population a symbol that immortalises the period of a system of racial segregation, racial oppression through apartheid, of a crime against humanity and of South Africa as an international pariah state that dehumanised the black population; and

The Old Flag is associated with the shameful apartheid policy with which most peace-loving South Africans, of all races, do not wish to be associated.

The court ultimately found that the Old Flag constitutes hate speech, and commenting on section 16 of the Constitution, and the right to freedom of expression, it noted as follows:

There are clearly two parts to section 16. Section 16(1) protects freedom of expression and specifies categories of the freedoms that are included under its protection, like freedom of the press and media etc. Section 16(2), however, excludes certain specified categories of speech from the protection of section 16(1). The excluded expressions can therefore simply not claim the protection of section 16 (1).Hate speech is an expression which is specifically excluded from protection by section 16(2)(c). Section 16(2)(c) does so by excluding any “advocacy of hatred that is based on race, ethnicity, gender or religion, and that constitutes incitement to cause harm.”

The court ultimately clarified that use of the Old Flag does not enjoy constitutional protection – it is regarded as hate speech, and does not fall to be protected in terms of section 16 (unless it is used in good faith for academic, research or journalistic purposes in the public interest, which is the carve out contained in section 12 of the Equality Act).

As the court in Masuku above should have done regardless of its finding, in this case, the court engaged with the Equality Act as a key part of the legislative framework flowing from section 16 of the Constitution (for hate speech related freedom of expression disputes).

The wording of section 10 of the Equality Act, however, prohibits only “words”, and in this case, words were not at issue – the use of a flag, which is considered as “expression” was at issue. Sensibly, after a thorough review of the relevant law, the court found: “The reference to “words” in section 10(1) must be given a generous and wide meaning going beyond mere verbal representations”.

The court further found that the Old Flag “demeans and dehumanises people on the basis of their race. It impairs their human dignity.” In sum, the court found that the gratuitous use of the Old Flag constitutes hate speech, harassment, and unfair discrimination in terms of the Equality Act.

Therefore, going forward, the gratuitous use of the Old Flag constitutes hate speech in that it is hurtful, harmful, and promotes hatred. However, there is no outright banning of the Old Flag – its use however is “confined to genuine artistic, academic or journalistic expression in the public interest” (in terms of section 12 of the Equality Act).

What does gratuitous mean? Basically, without good reason, or where its use is not justified. When will it be justified? As set out in section 12 of the Equality Act, only where its use is legitimately in the public interest.